The very fine paper

The Golden Dilemma (January 8, 2013)

Erb, Claude B. and Harvey, Campbell R.

Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2078535

discussed in this post How Did I Miss “The Golden Dilemma”? motivated me to revisit some really old books on gold that I had added to my Google bookshelf. I am always surprised by how centuries old finance and economics conversations still sound so relevant. Even more interesting is how many of the questions remain unanswered. My new favorite discussion on gold and deflation occurs in Gold and Prices Since 1873 by James Laurence Laughlin and starts like this (emphasis and links mine):

§ I. Much of the difference of opinion as to the significance of recent movements of prices is due to the fact that the value of gold is a ratio which varies with a variation in either of its terms. Whether commodities fall in relation to gold or gold rises in relation to commodities, in either case the value of gold has risen. The same phenomena, therefore, may be due to radically different causes. So that, admitting the fall of prices, it is said, on the one hand, that the rise in the value of gold is due to some cause affecting gold itself, such as scarcity; and, on the other hand, it is claimed that the fall in prices is due to causes connected solely with commodities, and not with gold.

The believers in the scarcity value of gold substantiate their position by reference to the falling off in the annual production of gold; the unusual demands for gold since 1873, by Germany, Italy, and the United States; stringencies in the money market; the increased use of gold in the arts; the claim that the fall of prices is general; the exceptional character of the depression of trade since 1873; the general existence of low wages, profits, and rents; and the absence of any progress since 1873 in the means of economizing gold and silver. These opinions have been prominently associated with Mr. Robert Giffen, the statistician of the English Board of Trade, and Mr. Goschen, the present Chancellor of the Exchequtr; while the evident connection of the main proposition with bimetallism has given it a semi-political character, and many supporters in both Europe and America.

§ II. Inasmuch as the rise in the value of gold since 1873 is in proportion to the fall of prices, it is a matter of some importance to look critically at the facts in regard to prices. With this object in view, the more important tables of prices since 1850 have been collected in the Appendix, with explanations as to the methods of computation, sources, and reliability. It is hoped that a comparison of the diverse methods and results of these tables will serve a useful purpose.

Hitherto, the figures of the London Economist for twenty-two articles have been almost universally used as evidence in regard to the movement of prices; but it is time that the worship of this fetich should cease.* Of late, much more trustworthy tables have been published.

I very much like the author's approach, which is to consider both the numerator and denominator in a price fraction and to gather as much data as possible rather than rely on one potentially flawed dataset. By page 3 we are already presented with this wonderful chart on prices/inflation in Great Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. These extra sources of price data allow us to frame the discussion much more objectively.

In the spirit of the author's approach, I wanted to reproduce the chart presented above in R and also compare the US Burchard's table with CPI and GDP deflator data from MeasuringWorth. I tried to take the easy route with OCR, but eventually manually entered the price tables from the appendix.

The chart was well done and really could not be improved beyond color and labels.

As I have mentioned before, MeasuringWorth is a wonderful source of long-term economic and financial data. I wanted to compare Burchard's US table of prices to MeasuringWorth's US GDP deflator and CPI. The Civil War significantly destabilized prices. The effect is much more pronounced in the MeasuringWorth data.

The author discusses the shortcomings of the Burchard prices in Appendix Table M.

An examination of the Finance Report tables indicates that they were not compiled with great care. The price of an article will run along without change from month to month; then, suddenly, it will rise or fall sharply. The prices of articles that normally would fluctuate together (pig and bar iron, butter and cheese) show a very loose correspondence. Moreover, the same articles do not appear from year to year. An article will be quoted for a number of years, will then disappear, and later, perhaps, will reappear…Notwithstanding these serious imperfections, we reprint Mr. Burchard's figures for the years 1850-84, since they are the only continuous figures of average prices in the United States.

The author organizes his remaining arguments into 8 additional sections, which I have titled. Also, I will give my favorite passage from each section. Interestingly, many of these same arguments apply directly to the MMT world of today with the only exception being the absence of a gold standard.

Section 3: The Supply of Both Money and Credit Must Be Considered

In truth, in society as it exists to-day, the general level of prices for considerable periods (sufficiently long to permit the effect of changes in the business habits of the community, or changes in the existing stock of gold, to be felt) must depend upon a combination of the quantity of money with the various forms of credit. The two are inextricably bound together. So, therefore, the level of prices (so far as it is affected by the offer of purchasing power) depends on the expansion or contraction of two factors, quantity of money and credit, each of which may change to a considerable extent independently of each other. Both may increase or diminish together, or the gain of one may offset the loss of the other.

Section 4: Other Events Affecting Prices

The extraordinary and exceptional demand for commodities in periods of war, at the very time of the great destruction of wealth, produced an unhealthy state of affairs; but on the outside all seemed fair, and men had begun to believe that prices were fated always to rise. The speculation in metals (see Chart II.) in 1873 was of an unparalleled kind…There were all the evidences of an unhealthy and abnormal condition of affairs. But the unchecked demand, when the actual power to buy had been greatly impaired, could not go on forever. When it was once found that men had been creating liabilities beyond their means to meet them, the end had come. The crisis of 1873 was the painful return to a consciousness of the real situation, after a prolonged fever of speculation for nearly twenty years, which had spread over many countries. The effects were the more serious because the disease had got such great headway.

Section 5: Improvements in Industrial Process and New Supplies of Commodities

The period following a great financial upheaval is naturally crowded with improvements in processes and in methods of lowering the cost of production. Necessity becomes the mother of invention. The extent to which producers have been driven by the fierce competition since 1873 to cheapen production leads to the inquiry how far the fall of prices can be accounted for by influences connected solely with commodities, and not with gold. If these influences have been widely extended, it will be strong evidence that the scarcity of gold has had less effect than some suppose.

Section 6: Analysis of Prices by Commodity Type

Whether to draw inferences as to a scarcity of gold from forty-nine articles, or to infer that gold was abundant, according to the prices of fifty-one articles, is an awkward dilemma for those who think that prices give direct evidence as to the quantity of money. As Forsell remarks, the theory of a scarcity of gold is incompatible with the rise * in price of so many commodities.

Section 7: Supply of Gold

From these figures, it will be seen that the reserves in the banks of the civilized world show a very remarkable increase in gold. Although the total note circulation was increased 29 per cent., the gold in the reserves was increased 75 per cent., while the silver was also increased 25 per cent. In 1870-74, the gold reserves amounted to 28 per cent. of the total note circulation, and constituted 64 per cent. of all the specie reserves. In 1885, the gold bore a larger ratio to a larger issue of paper, or 41 per cent. of the total note circulation; and, in spite of unusual accumulations of silver (in the Bank of France, for example), the gold formed 71 per cent. of the specie reserves. This is a very significant showing. What it means, without a shadow of doubt, is that the supply of gold is so abundant that the character and safety of the note circulation have been improved in a signal manner. In 1871-74 there was $1 of gold for every $3.60 of paper circulation.* In 1885 there was 11 of gold for every $2.40.

Section 8: Supply of Credit

Specie to the amount of 1800,000,000 has gone into circulation in the form of note issues, representing an equivalent amount of specie; but gold has not been economized by the use of credit in the form of notes. While the total circulation of these countries has increased 35 per cent., the paper has been much better protected…The paper currency of every country except Russia has gained in security, together with a large increase in many of the countries. The gold supplies have not merely permitted an enlarged note circulation, but have furnished a much better protection to that increased issue.

Section 9: Price of Land Labor

It will be recalled at once, in regard to rents, that a marked characteristic of the period since 1873 has been the opening up of new and fertile lands, whose products have been transported at a greatly diminished rate. But this in itself is a reason why lands in the older countries should be thrown out of cultivation, and why rents should be lowered. This phenomenon, then, can be accounted for on other grounds than the scarcity of gold…The fact that wages have risen tends to confirm the belief that the fall of prices is due chiefly to the introduction of improvements.

Section 10: Conclusion

To assume that because the fall of prices coincided with the demonetization of silver it was due to an appreciation of gold, without considering whether the coincident phenomena were traceable to entirely distinct causes, is to fall into the fallacy of post hoc propter hoc. The forces which fix the level of prices at any time, moreover, are far too complex to admit of the inference that, because prices have fallen seriously, gold has become scarce.

Gold and Prices Since 1873 by James Laurence Laughlin is a reminder of how our current is wedded to our past. I often feel like the unprecedented actions of the world's central banks have broken the link to centuries of financial history. Rather, it seems they have simply temporarily suspended the immutable laws of humans and money and maybe “The effects were the more serious because the disease had got such great headway.” will haunt us.

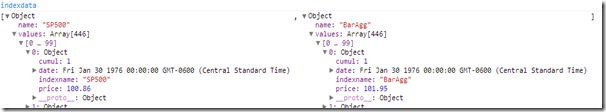

I ran out of time and could not do the visualization in d3. Anybody that is motivated, here is a way to get the JSON:

# for the ambitious and more motivated than me, here is how to easily get

# the JSON to translate the graph to an interactive http://d3js.org

require(rjson)

toJSON(list(Date = format(index(priceTables), "%Y-%m-%d"), as.list(priceTables)))

Post entirely generated from R markdown for reproducibility: